Article from Sophy Laughing

Sophy Laughing (Soph Laugh) is a California-born artist who specializes in the conservation, preservation, and restoration of antiquities. Laughing began making studies of portrait drawings after visiting the Maastricht Fine Art Fair. Inspired by masterpieces held in institutions and in private collection, Laughing began exploring drawings of the Old Masters.

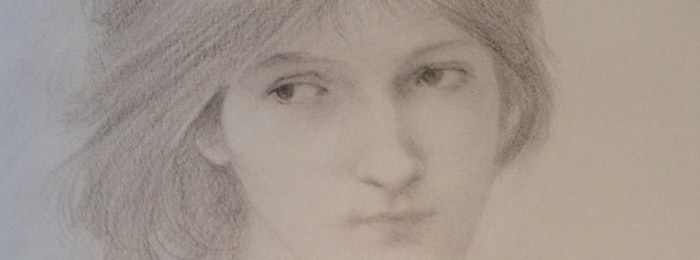

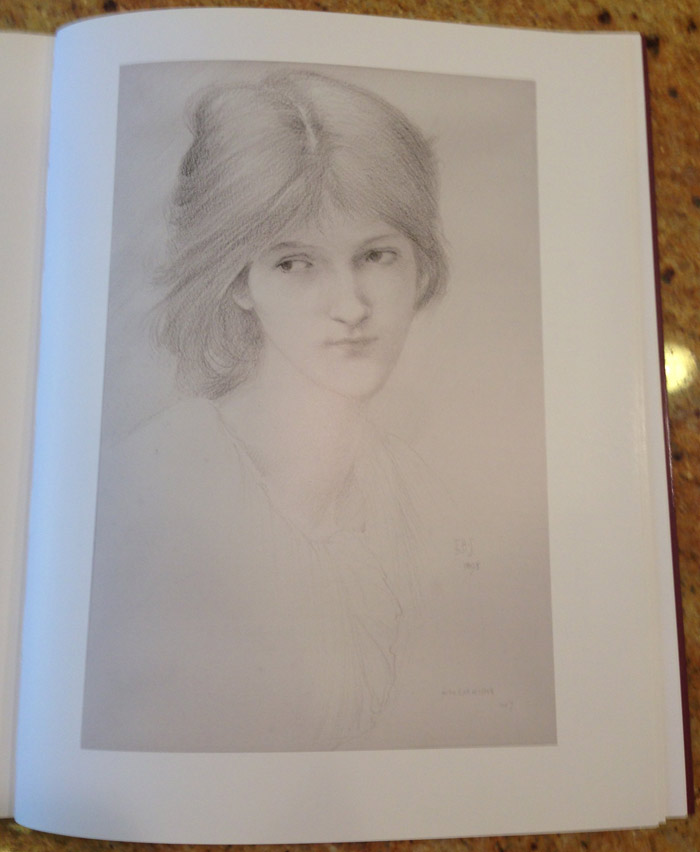

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones’ Study for a head for the painting THE CAR OF LOVE (1895) is one of Laughing’s favorite drawings. The drawing is a preliminary study for the head of a central female figure dragging the CAR mounted on huge wheels through the narrow streets of a city resembling Siena, which Burne-Jones visited in 1871. The male figures in the drawing are reminiscent of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, where Burne-Jones spent many hours studying and copying Michelangelo’s male figures. While the painting remained unfinished at the artist’s death in 1898, the features found in this beautiful head study became Laughing’s muse, shaping her perspective of ideal female beauty, as portrayed in pencil. So entranced by her face, as well as by the illuminated faces painted by Raphael, Laughing has since studied portrait drawings of the Old Masters.

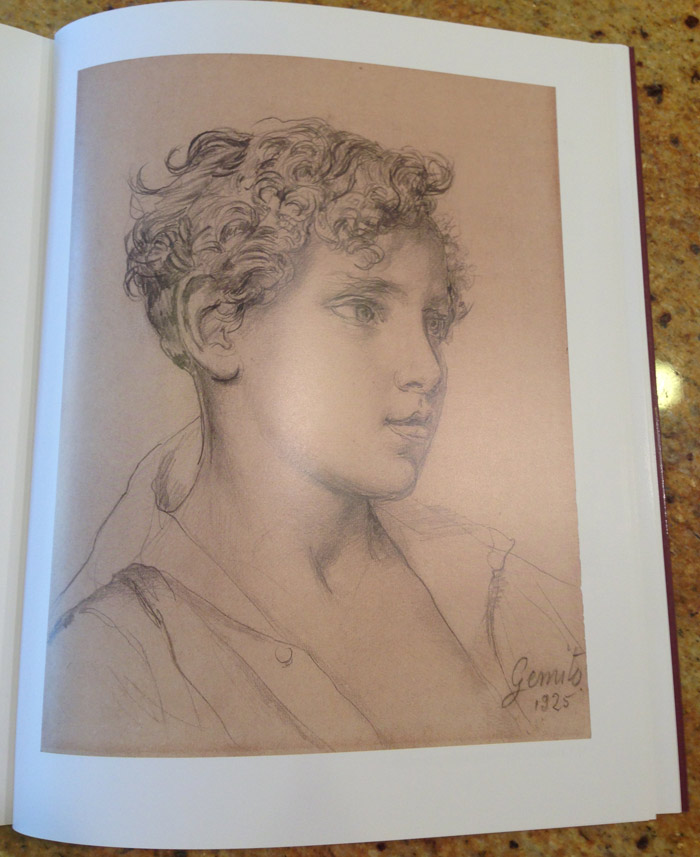

Another drawing that inspires Laughing is Vincenzo Gemito’s Portrait of a Young Boy (1925). Belonging to the vast production of Gemito’s graphic works, in which he cultivated an additional passion for sculpture, Gemito’s drawings are characterized by a severe and meticulous search for “truth” and the “natural”, through which movement, brightness, solidity and the sense of material are intensified. As Ugo Ojetti remarked, “Vincenzo Gemito, whether models or drawings, is a great portraitist” (Consolazio, 1951, p. 13).

The three-quarter portrait portrayed here has a hard look but the delicate trace of smile on his lips expresses his naïve tenderness. The pencil marks are thickened in his soft curly hair, which better define the chiaroscuro, the treatment of light and shade in drawing and painting, whereas stronger, sharper marks outline the figure tending toward the plastic rendering of the subject.

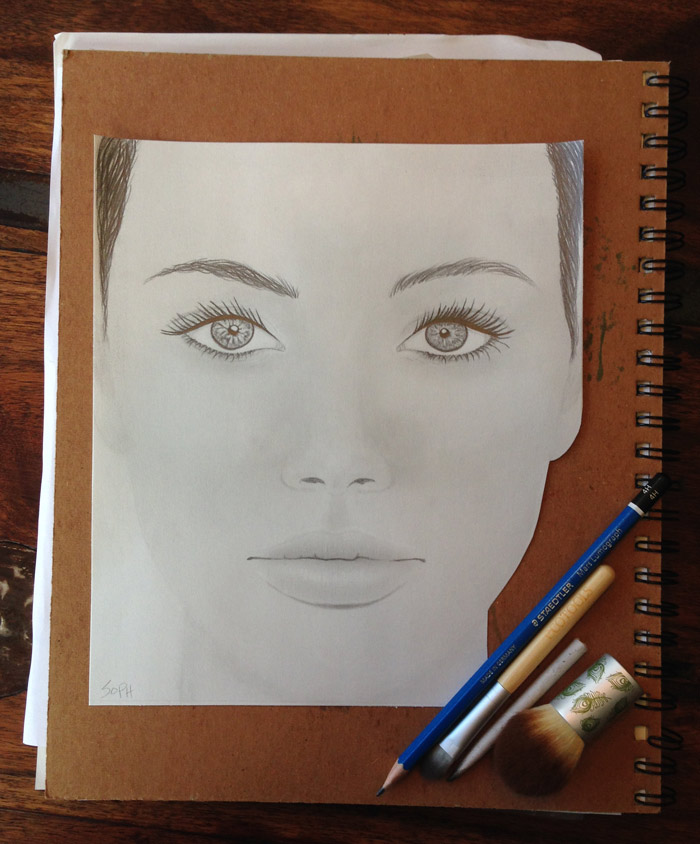

The effects Gemito achieved in contrast to light and shadow created by light falling unevenly or from a particular direction on the subject fascinates Laughing, who is presently exploring this technique. In Laughing’s Female Face Study, the light is shinning directly on the face, illuminating the face evenly. In future studies, Laughing aims to show the same face lit from a variety of angles.

In addition to experimenting with lighting techniques in portrait drawing, Laughing has plans to explore the aesthetic conventions that transform beauty into the grotesque. Exaggerating the features associated with traditional female beauty, Laughing has challenged herself to provide new perspectives characterized by suspending beliefs surrounding the ideal forms of beauty in an attempt to portray concepts associated with madness and hysteria.

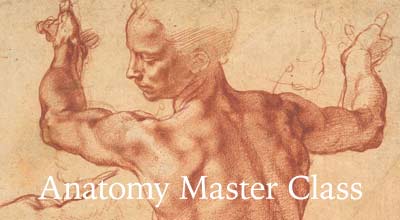

At the end of the fifteenth and during the sixteenth century, Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1512), abandoning humanistic ideals of the High Renaissance, and Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564) drew caricatures that are now referred to as ‘grotesques’. Leonardo, fascinated by people with “bizarre heads” (teste bizarre) reportedly followed them around in order to memorize their features, which he later drew and exaggerated in his drawings.

A philosophical humorist, Laughing aims to magnify and portray divergent human emotions in portrait drawing. This practice, compiling progressions of profiles, was practiced by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Hieronymus Bosh (c. 1450-1516), and Pieter Bruegel (c.1525/1530-1569) who stretched, shrunk, twisted, and contorted faces to represent human pride, vanity, avarice, and gluttony as symbolic allegories of human folly. The technique was continued by Daniel Hopfer (c. 1470-1536) and Peeter Balten (1525-1598), who drew prancing Morris dancers, evoking their jerky movements, and Vincenzo Camuccini (1771-1844), who depicted a contemned man to express his inner despair.

Art allows one to imagine, convey, and portray human engagement in a myriad of sentiments associated with human life, both real and imagined. Studies in ideal beauty and the various aspects of it from a variety of angles, as well as parodied studies similar to those expressed by Greek and Roman artists, not only provide us with new understandings of truth and beauty in nature, but also a visual understanding of our personal identification of images that convey behavior as we perceive it to be in waking consciousness, in our dreams, and in our nightmares.

Expunging on human nature being an inherent mystery, Montaigne said: “Those who strive to account for a man’s deeds are never more bewildered than when they try to knit them into one whole and to show them under one light, since they commonly contradict each other in so odd a fashion that it seems impossible that they should all come out of the same shop.” It is important that we recognize that in our many attempts to depict human sentiment, it is not the same as trying to make human sentiment intelligible. In this respect, artists must continually study the simplistic or traditional models against which human subtlety and shadows can be explored and discovered.

Philosophers explore two kinds of knowledge: rational knowledge and intuitive knowledge. Expressing these comparisons in art allows us to better order to compare and to classify the immense variety of shapes, structures and phenomena around us. No one artist can take all possible human features into account, but as a collective whole can select a few significant features to examine. Thus, artists construct an aesthetically intellectual map of human reality in which things are reduced to their general outlines.

Depicting rational knowledge in art is thus a system of expressing abstract concepts and symbols, characterized by the linear, sequential structure, which is typical of our thinking and speaking. In most art forms, this linear structure is made explicit by the use of light and shadow which serves to communicate the experience and thought in long or short brush strokes or pencil marks.

The natural world, on the other hand, is one of infinite varieties and complexities. From the ideals in beauty to grotesqueness, it is a multidimensional world that contains no straight lines or completely regular shapes, where things do not happen in sequences, but all together to create a complete composition. In thinking about portraits, we can think of the problems faced by cartographers who try to cover the curved face of the Earth with a sequence of plane maps. We can only expect an approximate representation of reality from such a procedure, and all rational knowledge is therefore necessarily limited.

The limitations of any artistic study obtained by drawing or painting teach us that as clear as is the paint on the canvas, art has only a limited range of applicability. For most of us, depicting reality or the reality of what we imagine is challenging. Still, it is the aim of nearly every artist to rid us of this difficulty, to portray ourselves through a variety of techniques and mediums, independent of the tools used to create them.

What concerns the artist is a direct experience of reality that transcends the eye and intellectual thinking, even sensory perception. In the words of the Upanishads,

What is soundless, touchless, formless, imperishable,

Likewise tasteless, constant, odourless,

Without beginning, without end, higher than the great, stable –

By discerning That, one is liberated

This liberation does not rely on the discriminations, abstractions and classifications of art in its many forms, but is always relative and approximate. What the artist sees might not be what the viewer perceives. The direct experience of undifferentiated, undivided, indeterminate ‘suchness’, a concept expressed by Buddhists, is the central characteristic of artistic studies and artistic experience.

During these studies on portraits, the intuitive mind seems to take over and can produce the sudden clarifying insights, which give philosophers so much joy as well as a seemingly infinite reason for pause. Art becomes a delightful medium by which philosophically inclined individuals, or individuals prone to deeper reflections on human nature, can explore without long lines of letters, the nature of knowledge as it relates to human experience insomuch as it can be portrayed by any given artistic endeavor.