Article from Slater Smith

Tempera painting was once the primary way of applying pigment on canvas, its only rival being fresco painting. Every Old Master made tempera from scratch in their workshop, along with the apprentices that gathered to learn what it took to be an artist. Mixing tempera was a very delicate procedure, admitting much room for error. Despite this, tempera reigned during the early Renaissance and for centuries prior, dating back into Egyptian times. With the advent of oil painting, the beautiful medium slowly died out.

Artists had to mix tempera themselves, as needed. The pigments, also ground from raw material, were combined with the binder, egg yolk, and distilled water. It was essential to get the proportions accurate, which slightly varies depending on the pigment. It dried quickly, sometimes on the brush itself, much like common-day acrylics. Too much paint would leave leftovers that could not be stored; only discarded. On the opposite end of the spectrum, not making enough tempera paint, would like lead to color inconsistency, as a second batch rarely matched the first.

Madonna and Child with Six Saints (Sant’Ambrogio Altarpiece)

Tempera on panel, c.1470, 170 x 194 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

Painters at the time used wood panels to apply tempera. Multiple boards of wood were layered to reduce the amount of distortion caused by the liquid elements of the paint. The boards were sanded down to smooth out the rough surface. This was not enough for the panels to be employed. Several layers of gesso were applied to give a smooth, white, nonabsorbent background to the brown wood. Gesso is still used today for similar purposes on the canvases bought at art supply stores.

The techniques used with the application of tempera can be related to the drawing process. In order to achieve the effects of light and shadow, hatching and cross-hatching had to be implemented, one layer at a time. Each successive layer would represent the darker or lighter planes of the subject. As said before, tempera dries in but only a few short minutes. One had to work speedily, before the fresh tempera turns to waste. That took a skillful hand and confident mind, making the paint difficult to work with. In addition, the color in the egg-based paint were relatively dull, mute, and void of spirit. Some religious pieces had gold leaf, thin squares of gold, surrounding the holy subject, typically in a halo. Carefully, the artist used tools that indented or shaped the leaf, creating decorative designs that brilliantly shone in light. The brief dehydration period and required discipline were some characteristics that led to the decline of tempera painting.

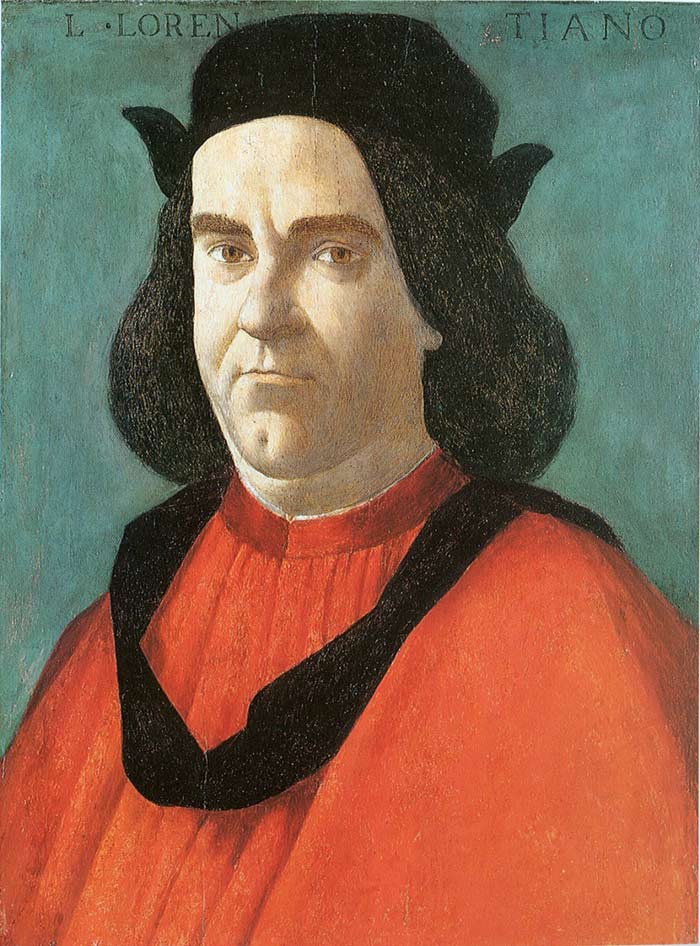

Portrait of Lorenzo di Ser Piero Lorenzi

Tempera on panel, about 1498-1500, 50 x 36.5 cm

John G. Johnson Collection, Museum of Art, Philadelphia, United States

When oil-based paints were introduced in the 1500s, temperas began to decline. Through glazes – and the later impasto – the artists of the time were able to create rich and varied tones, which did not dehydrate nearly as soon as in tempera. Hatching become unnecessary and painters could be patient and meticulous in their works. The image below, The Baptism of Christ, provides one of the most famous instances of oil over tempera preferences. According to legend, Leonardo da Vinci’s instructor, Andrea del Verrocchio, gave the young student the opportunity to paint the angel on the left. Willing to experiment, curious Leonardo used oil paint, a medium not yet introduced to his region of Europe, to render the angel. Upon seeing what da Vinci had done, Verrocchio decided he had been surpassed and refused to pick up another brush.

Oil on wood, 177 cm × 151 cm (70 in × 59 in)

Uffizi, Florence

Since tempera’s death, several artists have attempted to revive it. Alas, their effort bore little fruit and very few painters continue the legacy. Hopefully, tempera will not fade away with time, leading to it being confused with its oil counterpart.

Andrew Wyeth was an advocate of egg tempura, which he used to great effect in such works as The Helga Pictures and others. There are several other supporters of this technique, who achieve excellent results.

The position taken by this article is akin to the aversion to crimnitz.

Just because something is new doesn’t make the new superior.