Jim Piano

Draw what you know vs. draw what you see? It seems that if you are drawing a tree, you know there are leaves, but that is not what you see unless you are very close. So why would you draw what you know? As example, I know skull anatomy, but other than as general background help, I feel like I should draw the face I see. So why is the skull knowledge so critical to drawing that face?

Jim Piano

Dear Jim,

“Drawing what you know” refers to the constructive drawing principles, so the example with tree leaves is not relevant.

It’s very good that you know the skull anatomy; now I can explain how this knowledge applies in portrait drawing.

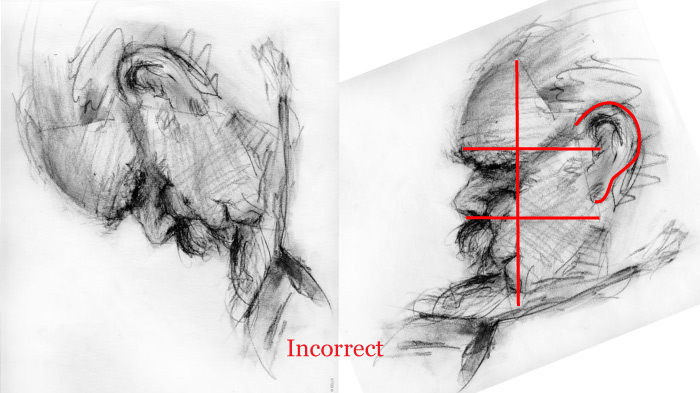

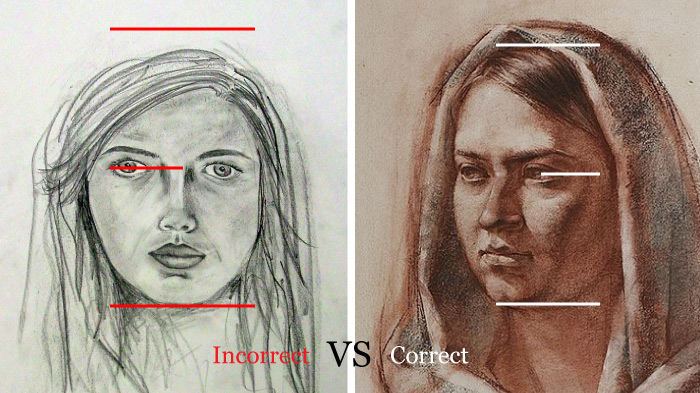

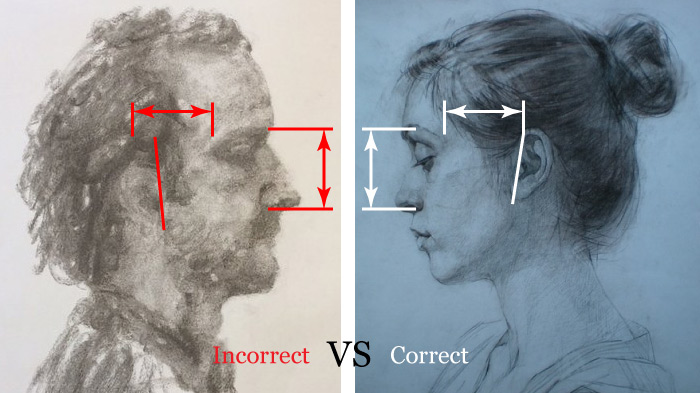

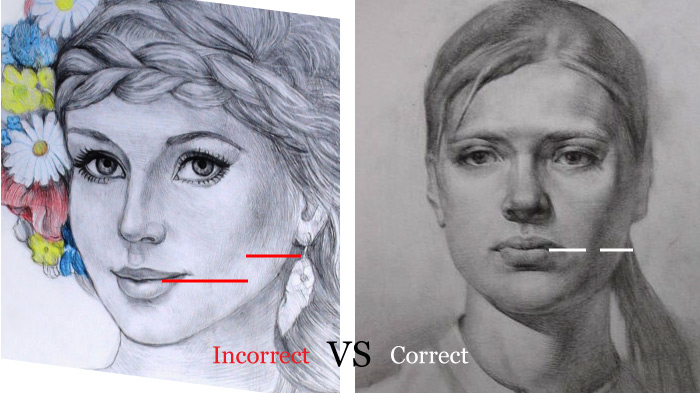

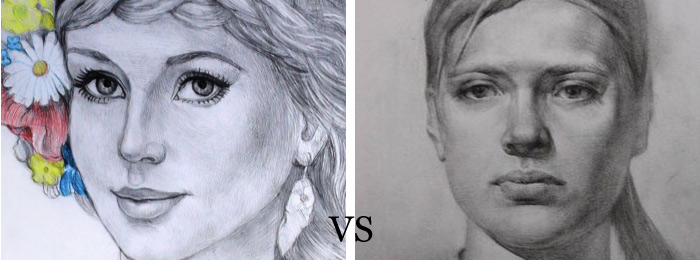

The thing is, people do not see what they don’t know. For example, in portraiture, beginners often make the same junior mistakes again and again – like placing eyes too high and not giving enough volume to the cranium section, drawing ears too small and too close to the back of the head, misplacing facial features, drawing asymmetrical faces, and so on. These mistakes have one thing common – students draw what they see without the necessary knowledge of construction, anatomy, and proportions.

Even when a beginner draws a portrait from life, and the model’s face is there to see – the student could measure and evaluate all proportions – mistakes are piled on instead, and a student can’t get an accurate likeness and realistic appearance of a portrait.

Why does this happen? It is not because of lack of observation; we see human faces on a daily basis our whole lives. However, somehow it doesn’t help in portrait drawing. Drawing what you see is not the best way to achieve great results.

Let’s come back to the skull.

If you know that the base of the nose is on the same level as the lower edge of cheekbones, you would apply this knowledge in your drawing, even though the bones are hidden under the flesh.

If you know that the atlas (the first vertebra of the spine) connects to the base of the skull close to the ear-channel axis (simply check in a mirror that ears stay on the same level when the whole heads tilts up or down), and that the top and bottom edges of an ear are aligned with eyebrows and the base of the nose, you would avoid many mistakes when a head is turned up or down.

If you know that the eye-line divides the head exactly in the middle from the top to bottom, and this rule works for every human head, you would not make the junior mistake of “seeing” and therefore drawing eyes too high.

If you know that the length of an eyebrow is equal to the distance from the base of the nose to the eyebrow and it is also equal to the distance from the eyebrow to the ear, you could use this knowledge to locate an ear correctly in your drawing.

If you know that the angle of the lower jaw is on the same level as the line between upper and lower rows of teeth, you would not draw this point too high.

I can continue giving such examples for quite a while, but I hope you get the idea ‘Why draw what you know’.

Best regards,

Vladimir London

Drawing Academy tutor

Great answer to the question “Why draw what you know”. It clicked in my mind that what I was doing up to today is drawing without the knowledge. I really would like to enroll in the Drawing Academy because my previous art teachers had no idea how to teach drawing. I spent several years of “learning” how to be creative without a single tip on how to draw portraits. It hurts to realize how much time was wasted, but I’m happy that I have found this drawing course!

Same question arises again and again. This can also be applied to any subject. Let’s take the example of the tree. Of course, a tree has branches, tree trunk, leaves etc. But, what if you need to draw/paint specific tree. One has to know the characteristics of several trees. If you are planning to draw mangrove tree and a banyan tree, you certainly need to know how do they look like in shape, height, width of the tree trunk, leaves etc. If they are seen from a distance, one has to know how do they look like from a distance. for eg. a weeping willow and an oak tree.

The examples you have shown are obviously beautiful sensitive pieces of draughtsmanship, but although I don’t disagree with you comments, I feel they could be misinterpreted. I would contend that the artists who have produced the other examples are not drawing what they see, but what they think they see, because they haven’t yet learned how to really look. What you describe as what you know to me is more of a way of helping people to see, rather than a set of rules about proportions etc. You could say it’s a kind of integrated prices – each part of the process, looking and knowing, building on the other. There is another point: faces in particular can be extraordinary and far from a classical ideal, which is where the real challenge begins. But of course you are right none of this is possible without a really strong grounding in drawing.

Vladimir:-

I have read many of your eloquent responses to students who wish to learn to draw well, in the traditional, realistic manner. Most of what you say rings true for me, a person who has practiced ‘life drawing’ continually, with live human models, though always too brief sessions, in both formal and drop in groups, since the 1970s. I, like many people of my generation, went to Art school in the 1960’s, but had little formal drawing or painting instruction while there. This was a disappointment and I complained bitterly at the time. My complaints were not entirely overlooked, and I, with two other like-minded students, managed to persuade the college authorities to set up a six week, six hours a day (weekdays) course to learn to draw and then paint the same pose from a live, elderly but spirited, model. This six weeks was the only useful period for me in a 4 year undergraduate course. Our tutor, David Ferguson, was the first post war winner of the RA Rome Scholarship in Drawing. He taught a variety of the sight size method, proportional size, constructing a notional ‘cage’ that exactly contained the models space and locating every ‘turning’ point on the model with the construction of horizontals and verticals refered to the cage location. This method, which required you to have quick and accurate mental arithmatic skills, especially with multiplying and dividing fractions, was quite technical and cumbersome, but it worked. After I graduated and depended on community type life drawing groups for practice, the poses were usually far too short to be able to use this method.

The difficulty I have with the course that you offer is that I cannot see how video instruction can help with the crux of the issue that faces students like me. I rarely had the opportunity to draw directly from plaster casts of the antiquities, a step on the path that you identify as critical. Where will I get these plaster casts from in order that I can be in the same room to draw them? You have already explained that drawing from photos or videos is useless, and this conforms to my experience. How will your course make it possible for me to draw directly from antique models?

I am not even sure that I want to train on antique plaster casts. One of my tutors at Art School, who had been through the traditional training you describe, told me ‘You know it wasn’t all as ideal as you imagine. After two years of drawing and painting from plaster casts, when I got on to live human models, I could not draw someone without making them look like a Greek hero or goddess in my picture. If I was drawing a live model and a limb went inconveniently off my page I drew a cross section through the limb as if it was an ancient statue that was incomplete. Everyone in my class drew so identically to the ideal, that we did not know whose drawing was whose when they got accidentally jumbled.

This raises one more point where I cannot agree with you. The exhortation to ‘paint what you know, not what you see’ is very misguided in my view. You are teaching an ideal which few people conform to. We should record the truth, ‘warts & all’ in my opinion, otherwise, you are teaching people to lie about what they see. We could not say in a court of law, ‘tell the jury what you know, not what you saw’, it would lead to terrible injustices. A few years back, I had a model in the USA who told me she had great difficulty lifting her arms above her head. She told me her school Physical Education teacher had arranged for her to see a muscle-skeletal specialist to determine what was wrong. The specialist had examined her and told her and her teacher that she was lacking the muscles that others had that enabled the arms to be lifted. In fact, he said, very few people have a complete set of muscles, nearly everyone is missing some but usually have alternative muscles that can take up the strain. Likewise, my osteopath told me that virtually everyone has identifiable asymmetries in their skeletons and musculature which rarely have significant consequences for their daily life, but were quite visible. I find asymmetries in virtually all my models. In one of your missives you said that asymmetries in drawings are signs of students drawing what they see and not what they know. How is someone to identify those asymmetries that give a particular person character, beyond a symmetrical ideal, if they do not trust what they see beyond what was portrayed in some ancient ideal? When the masters said ‘always let nature be your guide’ surely they meant the nature that you witness first hand, not the nature that is presented in an ancient statue. Besides, ancient statues are always stylized, you could never mistake the hair or beard on an antique statue for the real thing, as you see it, it is an understandably stylized version of what would be seen, we all undestand that the limitations of the medium call for compromises.

When you speak of ‘learning proportion’ in anatomy lessons you speak as if every skeleton had identical proportions, but you only have to look at the crowds walking in the street before you, to know that the ratios in length of the lower leg, the thigh and the spine are highly variable both between people of the same age and in one person from the cradle to the grave. There are no universal proportions in the human form, though there are limits to the variation. It is identifying these variations by seeing them that keeps life drawing interesting. If every person I had drawn had the proportions of a Greek hero or godess, I would have given up in boredom long ago. Although there is doubless skill in the beautiful drawings you do of idealized nudes, I doubt that even you would be happy not to be able to move beyond that to persons less idealized.

The following quote from Albrect Durer indicates, I think, that although he set up ideal schemes of proportion, he did not expect that he would always observe them.

The Creator fashioned men once and for all as they must be, and I hold that the perfection of form and beauty is held in the sum of all men. That man will I rather follow who can extract this aright, than one who wants to establish some newly thought-up proportion, in which human beings have no share. If I, however were to be attacked upon this point – namely, that I myself had to set up strange proportions for figures -about that I will not argue with anyone. Nevertheless they are not inhuman; I set them so much apart from each other in order that anyone can render account of it to himself and take care whenever be thinks that I do too much or too little in defiance of the natural shape – to avoid this and to follow nature.

Albrect Duerer (1471 – 1528)

Dear Chez,

Thank you very much for your comment. I do appreciate your feedback.

Yes, what you say about your art education confirms the decline slope it has been on in the West since 1960’s.

In my country, things were different and classical art school survived to these days. I went through it, and am considering myself very lucky to have such an opportunity.

Imagine how your education would be different if instead of only 6 weeks you would have full 4 years of proper art teaching and life drawing.

Our art school was not keen on the sight size method, you may check in this article why:

http://drawingacademy.com/sight-size-drawing-method

You also mentioned that after graduation your life drawing sessions were limited to “far too short” poses. Yes, drop-in sessions and life classes start with 2…10…30 minute poses. Why fast sketching it is not the best way to study life drawing for a beginner is explained here:

http://drawingacademy.com/how-to-get-the-most-out-of-a-life-drawing-class

I’m anticipating your next question about models, here’s what we advise to our students:

http://drawingacademy.com/how-to-find-models-for-drawing

You asked “How will your course make it possible for me to draw directly from antique models?”

I think you are misunderstanding the purpose of the Drawing Academy course. It is not about drawing antique models. It is about giving art students an understanding what constructive drawing is, how to use perspective in drawing, why in figure drawing the knowledge of proportions and anatomy is important, why golden ratio can be helpful in building better compositions, and so on.

We are not naive to think that an online course can provide the same experience that art students have in classical brick-and-mortar art schools that teach traditional art skills the right way.

About your comment “I am not even sure that I want to train on antique plaster casts” – that’s totally up to you. We definitely don’t want you to be trained. Educated – yes, but not trained.

http://drawingacademy.com/drawing-training-vs-drawing-education

I can only be sorry for your art tutor who had an erroneous experience with classical casts drawing. You confirm once again that even the “old school” in the UK had some erroneous teaching methods.

I think you also misunderstand the point of ‘paint what you know, not what you see’. A human brain is wired in such a way that we do not see what we don’t know. So drawing what we don’t understand is just a blind copying.

Here’s an example – if you don’t know that in figure drawing, diminishing in perspective sizes should not be depicted literally, you would make junior mistakes of copying distortions of photo-perspective that you see.

Do you know that medical students start their education with learning an absolutely healthy human body? Later on, they study all anomalies and diseases and how to treat them. The same in drawing. We advise to start with classical proportions and learn to see deviations from them that make every human body unique.

I hope this clarifies some points you’ve raised.

Kind regards,

Vladimir London

Drawing Academy tutor

many thanks! very useful , drawing is about learning to see! when i look at my drawings from a year before … i see that was very bad , learning from the live models without some theoretical principles make you not allow you to draw from memory or imaginagion, it exist many levels of art , for a beginner is absolutely necessary to understand proportions, measures that was used like guides from antiquity , michelangelo painted the sixtine chapel, alone, without any model , he have studied anatomy for many years, that was all learned for him! one can not see always the third dimension in the start, is why vladimir tell _ draw what you know, not what you see _ … beginners see flat forms , and havent knowledge to render the three dimensional forms !drawing from live models are for more leveled artist i think ..