Article by J. Danilo Garcés Rodríguez

I thought about this one a lot. When so much has already been said, when almost every corner and detail of a subject has already been study so thoroughly as the life and work of Vincent van Gogh has been, is really hard to just start writing without thinking that whatever you’re about to say probably has been told a thousand times already and you don’t even know if the way you are going to tell it will be worth reading at all. As a result of these thoughts I found myself looking in doubt to the empty page for minutes at a time before closing it and giving up to the incapability of creating for another day. Days passed on like this and I was about to quit trying to write about Van Gogh.

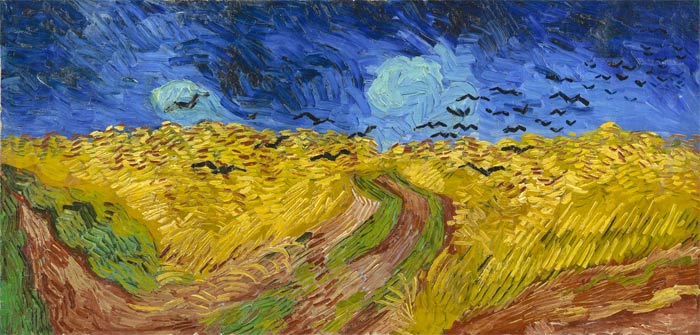

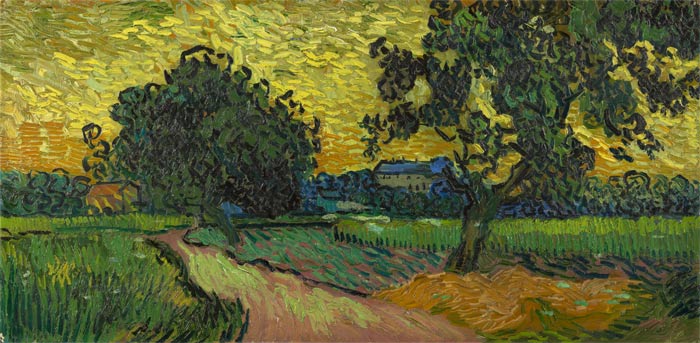

But just before quitting and start looking for a new subject I decided to take a last look at some of his paintings. First I looked at the Kingfisher by the waterside and remembered the influence that Japanese art had on his work, how he talked about it in his letters as a new way to perceive reality that one could not help but feel happy about. Later I looked at The Wheatfield with crows, this one with its infamous reputation, its ominous feeling and at the same time so full of serenity, just imagining it as I write this makes me feel the tranquility of the wind blowing in the yellow wheat fields making them sing that rattling song of trembling leaves, almost inviting you to walk into the painting through the open path into a peaceful sleep.

Seeing this painting and knowing how much he had to struggled throughout his life, made me wonder for an instant what kept him painting? What was it that he found in art that even after he embraced with sadness the idea that he was never going to be recognized by his paintings (something we know it’s not true but he died certain of) kept him going outside every morning to paint the trees, the flowers, the fields, the sunsets and the streets? With this question in mind I realized that I didn’t want to just talk about Vincent van Gogh, what I wanted to do was to understand his resolve, the passion that describes him, and hopefully, learn something. For this I didn’t want to talking about his childhood or his parents or the so well-known love related problems he had throughout his life -even though in those one can perceive much of his capabilities for resolve-. So I decided to star at the middle of his life.

Borinage: Poverty among the miners

“Around the mine, there are their miserable houses, with some death trees completely smoked, files of bushes, piles of trash and ash, mountains of burnout coal, etc. Maris would have painted an admirable picture of it”

When Vincent was around 25 years old he wanted to be a pastor. He traveled to Borinage, coal mining town, to preach as a missionary. He was hired for six months but after that his contract was not renewed; in that time, he lived as if he thought that to be able to help those poor people find some solace in the word of god he ought to be just as poor as them. And so he set himself to do it. Donating the cabin assigned to him by the church to an old lady and living in the same precarious conditions as the rest of the inhabitants of the town.

If one were to ask why’d he do that; why would he choose to put himself through such conditions when there was no need to, what could be answered? Maybe that his abnegation and faith pushed him to the limits of his resolve to give himself to others but is that enough? Is that really a reason to choose hardship? Was he really helping anyone by going hungry? I cannot help but wonder if that desire to help others over himself wasn’t just an excuse… to forget about himself.

I decided to read the letters that he sent to his brother in that period of time and I found this: “I’m a man of passions, capable of more or less senseless things, of which I repent halfheartedly. It occurs to me often that I speak and act with precipitation when the better thing to do would be to patiently wait” this was my first hint to his spirit, but it didn’t explain his actions, in fact his reasoning, no matter how much I try to justify it, seemed that of a mad man; his abnegation to his job was crazy not because of how much he tried to help others, but because he didn’t seem to care for himself.

Not soon after he left Borinage he wrote to his brother about the cage he felt he was living in, incapable of finding something to make himself feel useful. Here I understood that it was that feeling, that yearning to be part of something, to not be the outcast he felt himself to be, that pushed him to try his harder to help those people, but at the end none of it mattered. The church dismissed him for disgracing the honorable image of a servant of god by living in such lowly conditions and his career as a preacher came to an end. But from this little episode of van Gogh’s life I was able to start to understand what was it that he meant by his actions. And what was it that Antonin Artaud, the French poet, meant in his essay about him when he wrote that “Vincent was a suicided by society”.

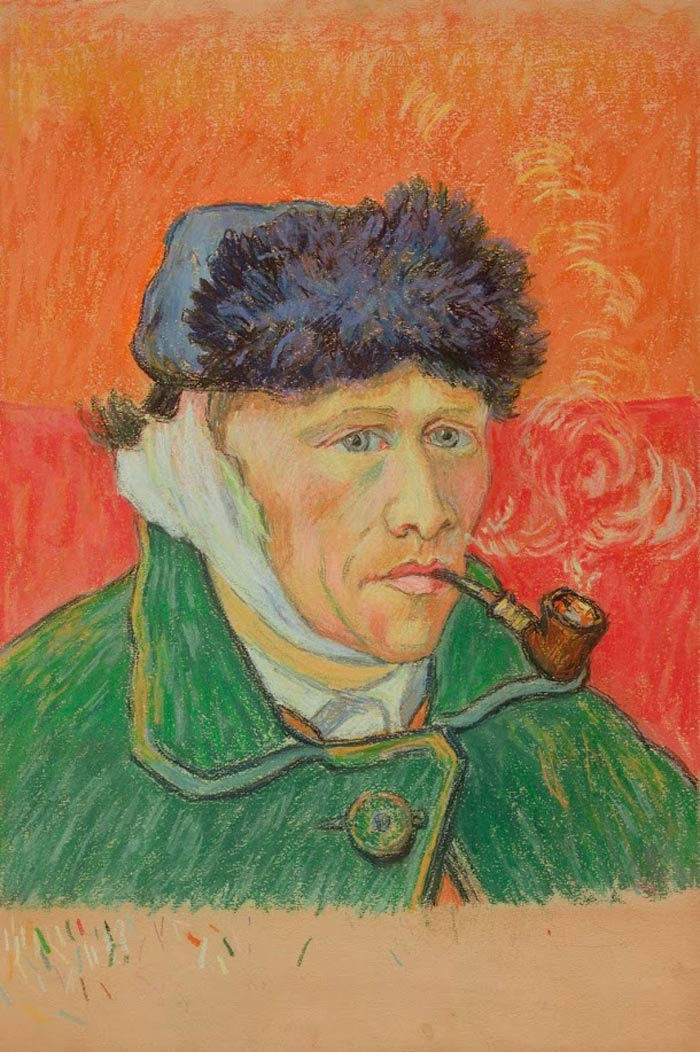

Bakumatsu the history of Japan in his brushstrokes

Eight years after the episode in Borinage, Vincent Van Gogh was living in Arles. He had finally decided to become a painter after his failure as a preacher and some of his early pieces represented the life of the coal miners he lived with like the in the potato eaters in which he portrait a family at the table illuminated by dim light surrounded by the coal dark night. But it was in Arles that he developed his characteristic vibrant stile and showed his profound abnegation to art. He left his house every morning to go paint the town and its outskirts until dawn, and then he would just go home and keep on painting. He was still poor and living in precarious conditions and not soon after he would be death, but in that short part of his life, he was hopeful, and loneliness seemed to have finally make peace within himself; all he cared about was the colors of the leaves and the night lights that illuminated the town. Hope, maybe that was it, maybe that was the reason I kept on trying to write about him despite how hard it was, and the reason he kept on painting. We both had a goal, something we wanted to achieve through this effort… this idea soon faded. I don’t really believe that hope is the reason I’m still trying to find the right combination of words to describe that something that pushed me in the first place to try to write about Van Gogh, and I know for a fact that it was not hope the thing that waked him up every morning to go paint for another day and the day after and the one after that. No, it was not hope for I know he lost it all after Arles, after his fight with Gaugin, after his stay in the mental asylum. Even thought that, he kept on painting and at this point I think I know why.

Antonin Artaud, the French poet, wrote an essay about the death of van Gogh in which he describes his own 9 years long experience in a mental asylum and how he found that the ones responsible for the death of van Gogh were the doctors and the society that surrounded him. He calls Vincent the suicided by society describing his death not as the moment Vincent lost himself but the one the world could not take him no longer. It wasn’t Vincent the one who pushed the trigger, it was the whole world that couldn’t bare the weight of a person set to live life in his own terms. And so, I found my answer: It was not hope the thing take pushed him to paint, far from it, it was the freedom he found in letting go of desires and expectations of achieving anything beyond the joy of painting itself that allowed him to keep on doing so despite of everything. He found in his last years that that which made life valuable and meaningful was the very thing that filled his own life with joy. For him it was painting, and he had done it for years, he had done it to his hearth content a now he was tired.

Bakumatsu is a Japanese term that refers to the period of war and conflict that passed before the opening of Japan to the world, it would also be a good term to describe the life of Vincent van Gogh as a period of war and conflict before the opening of the world to his work.