Article By Juhi Kulkarni

An article to understand Vincent Van Gogh through his letters and observational drawings of particularly trees.

“Drawing is at the root of everything,” Vincent, (June 3, 1883)

Vincent Van Gogh’s reverence as well as gratitude towards nature is apparent throughout his letters illustrated by drawings. Amongst the thousands of drawings Vincent did, trees fascinated him since early 1875 , as his art pursuit began from his mid twenties, leaving lasting impression on his life leading to most profound understandings and erudition. “Post was his main communication with the world outside. His charm, and intellectual power – which comes through so strongly in letters – functioned better at a distance. Face to face, almost everyone – found his company too much,” Martin Gayford writes, “To comprehend the complex thoughts and associations in Van Gogh’s mind, it is necessary to put his letters and paintings together. In that way, we can get extremely close to him: near enough to register the surging highs and lows of his emotional thermometer, to follow his swirling thoughts, almost to hear his voice.” From 1872 to 1881 Vincent wrote around two hundred letters to Theo, from Northern Europe, which contained the description of various foliage. Anna Suh writes, “Foremost among there is his ability to find solace and inspiration in landscapes and nature…although Vincent was eventually to renounce his religious beliefs, his love for nature was to prove more long lived.” During these years he was more fascinated with rural life and manual laborers but we do see in certain loose sketches his inclination is beginning to grow towards nature, as it gave way to his new aspiration to become an artist. In his letters to Theo, Vincent writes, “Am often sketching till late at night, to record some souvenirs and strengthened my thoughts, which are spontaneously aroused when I see things” , this seems to bestow on him solace in difficult times of loneliness and the act of observing stated to engulf him.

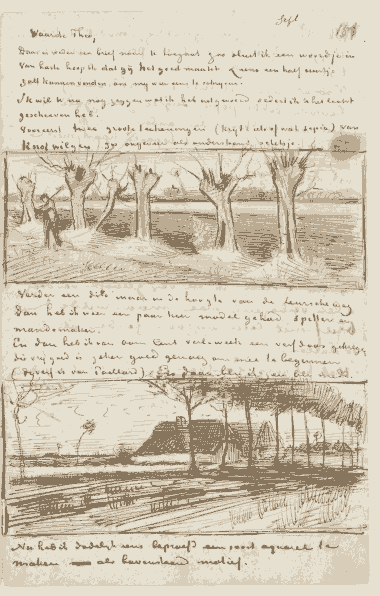

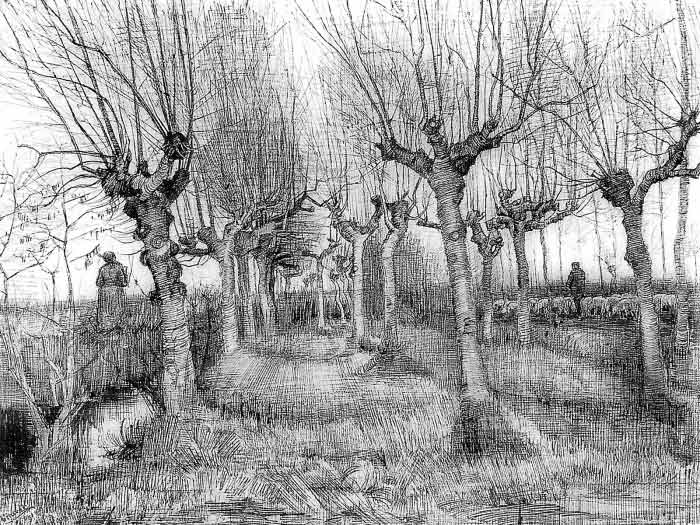

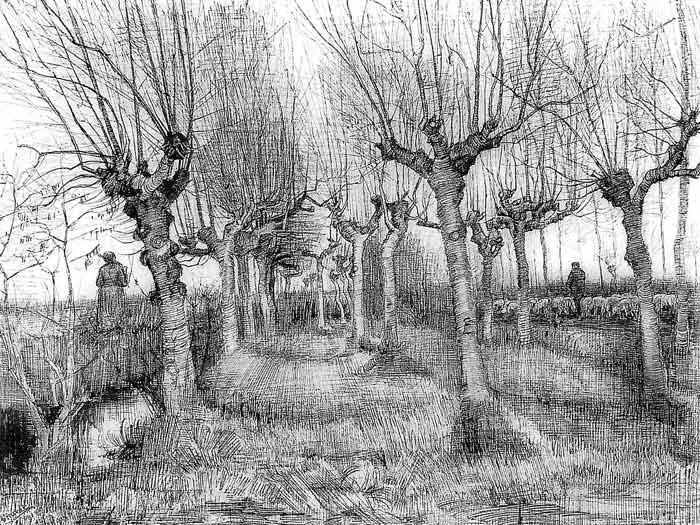

Trees began to make an appearance in his sketches as subjectively inconsequential but appropriate to add something to the letter he was sending to Theo to subconsciously mark himself as an artist. Vincent writes, “First of all two large drawings of pollard willows- more or less like the sketch below. Next a similar one, but oblong, of the road to Leur…And now goodbye, I have walked a long way today but I did not want to let the letter go without enclosing something.” With the second sketch we can also observe that Vincent had now slowly begun to gain control over the complex aspect of addition of perspective. Eventually as he began to show progress in skills of drawing, “There has been change in my drawing, both in my way of doing it and in its result….I have learnt to measure and observe and to look for making lines so that once seemed desperately impossible to me is slowly beginning to be possible” , Vincent writes to Theo. Ann Dumas observes his letters and sketches saying, “What comes across is his incredibly intense response to nature – a kind of epiphany – an exaltation of nature that never gets tarnished. When he was young, he wanted to be a preacher. Then he channels his religiosity into his art.” John Berger writes, “He is loved, I said to myself in front of the drawing of olive trees, because for him the act of drawing or painting was a way of discovering and demonstrating why he loved so intensely what he was looking at, and what he looked at during the eight years of his life as a painter, belonged to everyday life.”

When he moved to Hague in January of 1882, after a fall out with his parents, his personal life was in turmoil by getting involved with an unmarried woman. However, as an artist he was engrossed with technical aspects of different media, as well as question of perspective, colour, light and shade. Despite of social isolation he continued to produce many drawings working at a brisk pace. He developed strong independent thoughts and rigid opinions on the importance of drawings as a primary skill and seemed to experience a little necessitate for formal drawing. During this time, he began drawing landscapes profusely that added to his creative skills of visualization and perspective, in his letter to Theo he says, “I have been hard at work, and I am busy from morning till night. I carry on drawing these small town views almost daily, and I am beginning to get the hang of it.” As his obsession with nature grew so did his observation skills, his vivid descriptions are allegory to what he saw as he began to have a greater confidence in his drawings, “When I see how several painters I know here few struggling with their watercolours and paintings so that they can’t see the solution anymore. I sometimes think: Friend the fault is in your drawing, don’t regret for a moment that I did not go in for watercolour and oil painting straight away. I am sure I will catch up if only I struggle on, so that my hand does not waver in drawing and perspective”, he writes to Theo.

The years between 1884-87 saw in his life a lot of development, his helpfulness during his mother’s convalescence led to a rapprochement of sort with his parents, but after his father’s death, being sucked into another controversy, he had to relocate to Antwerp. His stint at the Antwerp Academy did don’t last very long and in March of 1886 and even though at that moment, his relation with his brother was strained, he showed up in Paris unannounced. However, his drawings were getting more complex and intricate and no longer just mere sketches. He says to Theo, ” For the current month I have already got the following drawings, Winter garden – pollard birches – lane of poplar – the kingfisher.” With his technique of drawing getting more proficient his works looked more secure and intense. He started to use various hand gestures, strokes and his tools confidently. Evidently this gave a big boost to his self-esteem. He writes to Theo, “If I have any self confidence about my work, it is because too much effort is spent on it to believe that nothing could be gained by it, or that it would be in vain. And again, I just shrug off the generalities most art critics increasingly appear to lapse into.” He became self absorbed and isolated with the act of making. He writes to Theo, “Now there is not a day that I don’t make something or other. Just by learning as I go along. Every drawing made every study painted means a step forward….To learn to look at the landscape at large in its simple likes and contrasts of light and dark. My study is not yet mature enough for me but the effect moved me, and as far as light and dark goes, it was as I draw it for you here.”

John Berger writes, “I can think of no other European painter whose work expresses such a stripped respect for everyday things without elevating them in some way…He became strictly existential, ideologically naked and from this nakedness of his which his contemporaries saw as naivety or madness came his capacity to love suddenly and at any moment what is saw in front of him. Taking a pen or a brush he then strove to realize, to achieve that love. Lover-painter affirming the toughness of an everyday tenderness we all dream of in our better moments and instantly recognize when it is framed. Drawing like these were not so much preparatory studies as graphic hopes; they showed in a simpler way – without the complications of handling pigment- where the act of painting could hopefully lead him. They were maps of his love.” By the summer of 1888, Van Gogh expressed more confidence in his methods, which he called crude even garish, still sought to strip his art down to essential in both composition and colour, and spoke admiringly of Japanese prints as models in his endeavor.

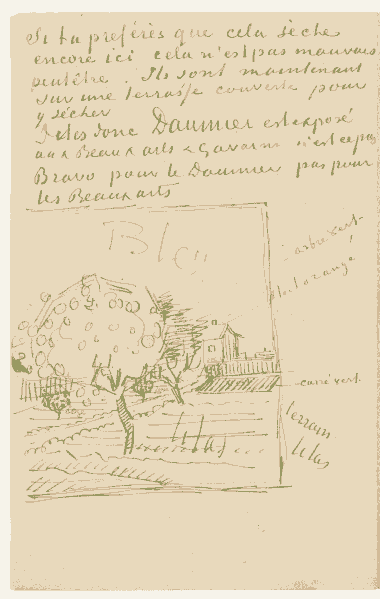

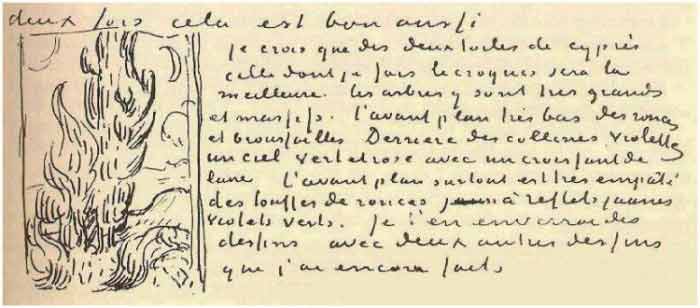

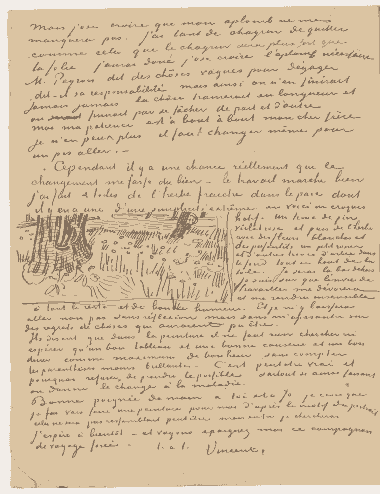

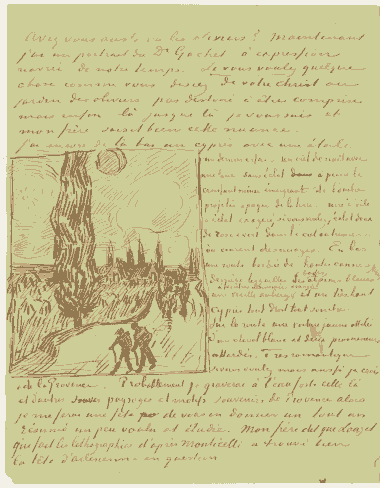

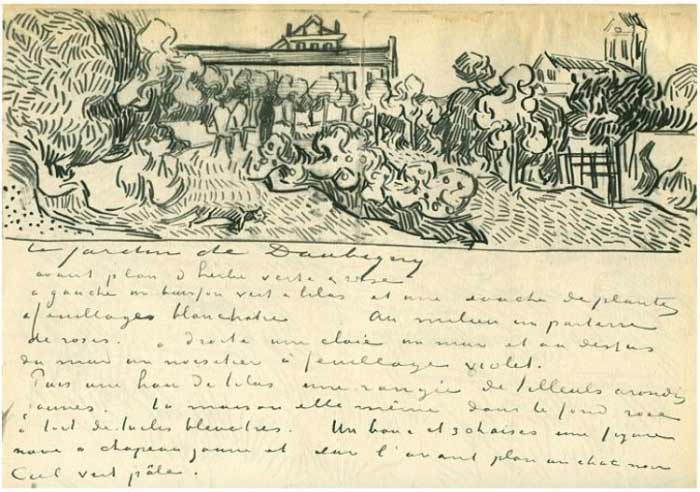

Slowly but certainly Vincent stated to use these sketches as a base for his paintings, which were to come, in comparison to this day photographic references used by many artists. Vincet writes to Theo, “Here is a sketch of an orchard tree that I’d planned specially for you for May 1. It’s absolutely simple and done at one go. A whirl of impasto with the faintest hint of yellow and lilac on the first white clump.” Martin Gayford writes, “In many ways the letters mixes words with images, as was the case with his discussions of the cypresses, where he added drawings to explain what he was describing. All that was missing in colour and that he supplied in words – literally in some places, where he made notes on the drawing to indicate the colour he was painting. Van Gogh made associations with what he saw, which is generally apparent only through his letters. Van Gogh’s was paper existence in double senses.”

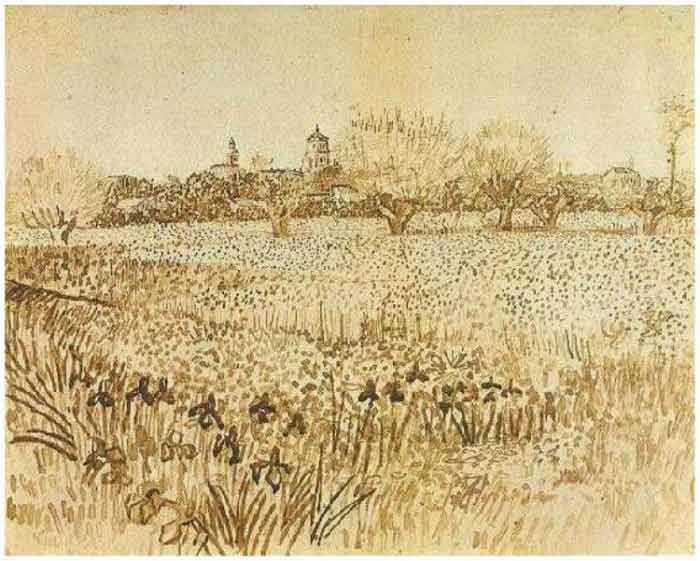

Vincent drenched into work, despite the discomforts as he moved to the town of Arles in late February of 1888. He was always inspired by the rural living and here began his prolific period that was exulted only with his death. “If they don’t cut the meadows. I’d like to do this study again, as the subject was truly beautiful and I had trouble finding the right composition.” , a sense of exigent reverberates through Vincent’s letters now as if he is demanding to accomplish everything in a given moment, quite often frustrating to rush against time, “What’s always urgent is the need to draw – whether directly with the brush or using something else, such as a pen – one can never do enough. I am not trying to exaggerate the essential and leave the ordinary deliberately vague” Vincent writes to Theo. By summer of that year, Van Gogh began to show signs of fatigue and vehemence but began to find deeper meaning through his work. He writes to Theo, “Don’t imagine that I’d remain in such a feverish state artificially; you have to understand that I am in the midst of complicated planning. These things are indeed so, but this eternally existing art and this revival — this green shoot growing from the roots of the old felled trunk — these are things so spiritual that a kind of melancholy remains with us when we reflect that at less expense we could have made life instead of making art. You really ought, if you can, to make me feel that art is alive, you who perhaps love art more than I do.”

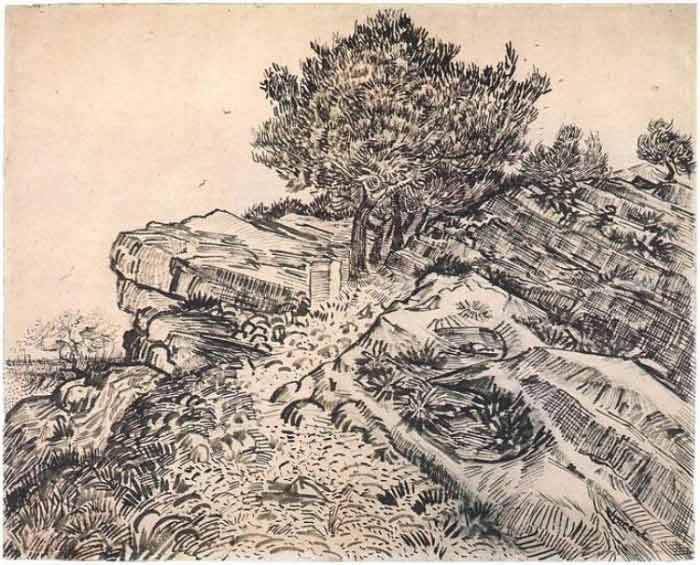

Mont Majour had an important place in his life. He often wanted his friends Bernard and Gauguin to join him here, and very often wrote letters to them describing the beauty and solace of the place. However the wind constantly disturbed him and he got quite often irritated with the fact that it was becoming a hindrance in his work. Vincent produced few of his most stunning pieces in his time period. “I wish everyone could come down to south like me…It’s strange, one evening recently at Mont Majour I saw the sun setting red, its rays falling among the trunks and foliage of some pine trees growing among the pile of rocks, colouring the trunks and leaves fiery orange…what I’d like to do is a panorama…I’ve been to Mont Majour at least fifty times looking at this flat landscape…..What a picture I could make of it if it weren’t for this confounded wind. That’s upsetting thing here, when you set up your easel somewhere. And that’s why my painted studies are not as finished as my drawings; the canvas is always shaking.” Vincent wrote to Theo.

Arles: July, 1888,Van Gogh Museum,Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Europe

During the fall of 1888, during a bout of nervous exhaustion his frenetic output lessened somewhat, still insisted upon painting only from life. In late October Gauguin arrived, but his stay lasted only nine weeks during which despite many pleasant exchanges the two men argued terribly, during their final dispute in fit of temper Van Gogh severed his ear lobe, and traumatized Gauguin fled Arles. Vincent wrote to Theo, “I think there is some serious problems still to be over come here for both of us (Gauguin and Van Gogh), but these difficulties are inside ourselves than anywhere else.” Even with onset of such hysterical behaviour Vincent remained true to his art. Vincent writes to Theo “it’s nature that I feed on. I exaggerate; sometimes I make changes to the subject. Nevertheless, I don’t invent the whole picture, on contrary I find it ready made in nature but in need of unraveling.”

Describing the intensity of his work John Berger writes about Vincent’s “The gestures comes from his hands, his wrists, arm, shoulder, perhaps even the muscles in his neck, yet the strokes he makes on the paper are following the currents of energy which are not physically his and which only become visible when he draws them. Currents of energy? The energy of a tree’s growth, …The pattern is like a finger print.” If John Berger is right, that is what set Van Gogh apart, where one artist saw nothing but stubble, Van Gogh saw so much beauty that it left him speechless. More than that, where one artist saw emptiness, Van Gogh saw eternity. “In all nature,” he once said, “I see expression and soul.” One moral of the story is certainly this, if a field of stubble stretching to the horizon moves you, you will never be without something to passionately draw or paint.

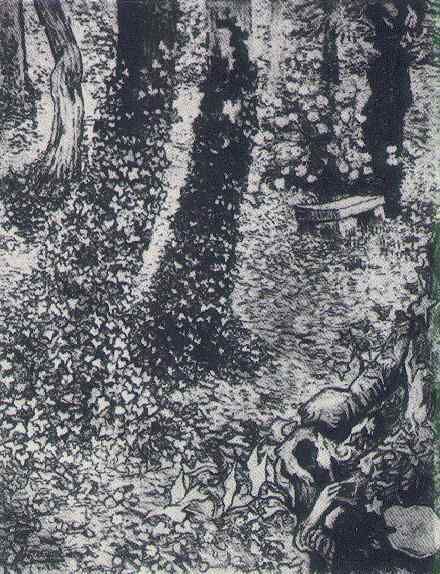

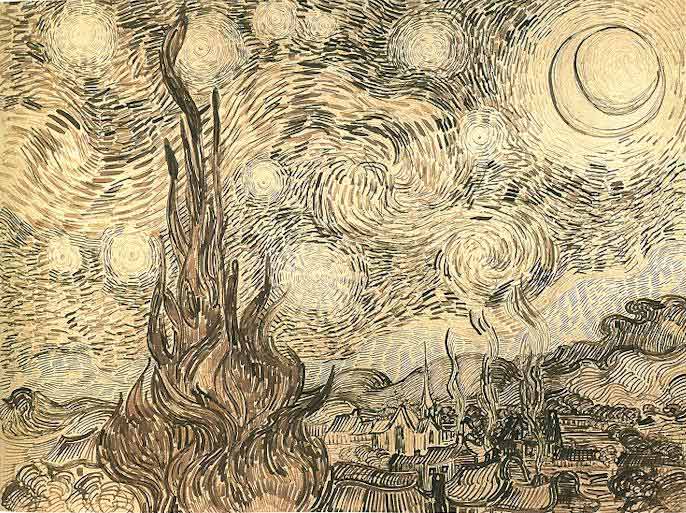

Oil on canvas. Saint-Remy, May, 1889. Location unknown

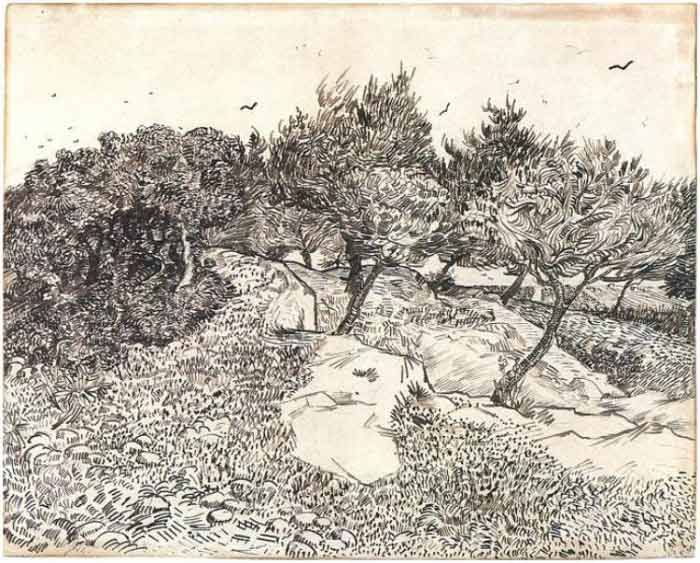

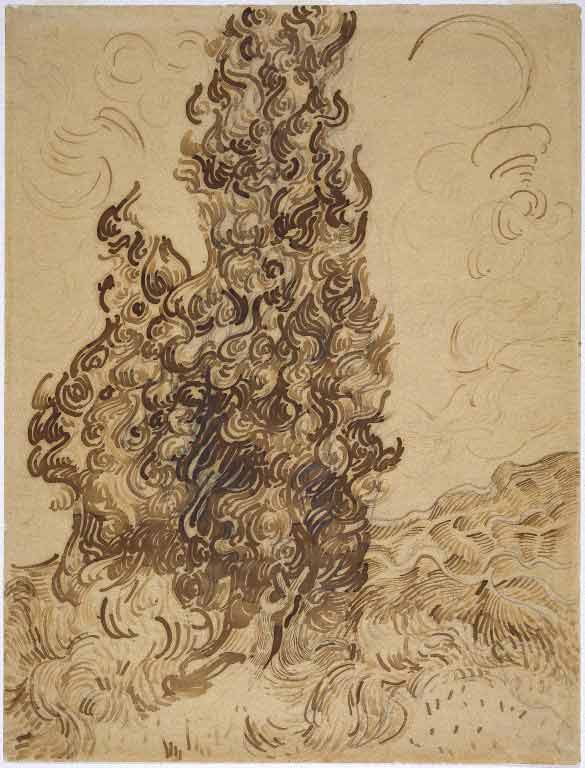

Recuperated from his ear cutting incident Vincent left the hospital in January 1889, he made several copies of summer sunflowers and a number of composition of still life paintings. After few more relapses Van Gogh decided to relocate to an asylum in nearby St.Remy. Here his brushwork became more animated and his painting took on that surging quality that is uniquely Van Gogh’s. During this time he made his most famous paintings including the Starry Nights and his vibrant studies of Cypress trees, Wheatfield and Olive groves. In fall he started an ambitious series translations of artists like Delacroix and Rembrandt, in September his works were exhibited in a group show in Paris to favorable reviews from both critics and his fellow artists. Kimmelman observes that, “the drawings translate sky, rocks and plains into a swarm of swirls, dots, jabs and scratches. Foaming, cable-knit patterns imply the heaving gusts of wind rustling olive branches and bending gnarled olive trunks; whispery, microscopic speckles, endless numbers of them, mimic the quality of dull light on receding fields as they evaporate into the horizon. As he kept reinventing drawing, he also found himself.”

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Europe

Ann Dumas comments, “In a sequence such as this viewers can virtually see Van Gogh’s creative processes in action…the letters have made look at his art differently. Now I see that both his words and his paintings have the same immediacy of expressions. In the swirling forms and the sky of painting like cypresses, we can see the way the brushwork illuminates the whole composition and is an extremely direct response to what his sees and feels. The two drawings and oil painting were all made around 25th June 1889 and depict an almost identical clump of swirling conifers with a crescent moon above and the Alpilles mountains in the background- but each has small differences. The position and the size of moons shift in each image. Technical analysis shows that he didn’t necessarily didn’t do the letter and drawing after the painting it was more dynamic, he might have worked on them all together.” His artwork and methodology now had reached its peak and Vincent had got a hold over his craft fully. We can see the underlined confidence in his strokes and movements, and effortlessness in his expression of love in art.

Regardless of these promising signs and reassurances to Theo he preoccupied with morbid thoughts in nostalgia for the North. Still working like one possessed, Vincent suffered yet another attack in late December. In his art, as his obsession for Cyprus grew so did the complexity of his drawings. Vincent writes to Theo “There is no news to write as every day is the same, the only idea I have are thinking that wheat field or a cypress tree is really worth looking at closely, and that sort of thing…The cypresses continue to occupy my thoughts: I’d like to do something with them like a painting of sunflowers, because I’m amazed that they haven’t yet been done in the way I see them. They have beauty line and proportion like that of an Egyptian obelisk…And the equality of the green is so distinguished….. I think of the two canvasses I’ve done a sketch of here will be the best. The trees are very tall and solid.” His spirit seemed to uplift with drawing. He writes to Theo, “Well, and yet it was in these depths of misery that I felt my energy revive and I said to myself, I shall get over it somehow, I shall set to work again with my pencil, which I had cast aside in my deep dejection, and I shall draw again, and from that moment I have had the feeling that everything has changed for me, and now I am in my stride and my pencil has become slightly more willing and seems to be getting more so by the day. My over-long and over-intense misery had discouraged me so much that I was unable to do anything. I cannot tell you how happy I am that I have taken up drawing again. I had been thinking about it for a long time, but always considered it impossible and beyond my abilities.”

Vincent’s drawings in his last three years have had a very strong impact on his art. Especially the ones he made with pen and ink. The quill and reed pens held only a small amount of ink. This meant that his drawings were composed of a myriad of short strokes because long strokes were impossible and he was necessarily dipping his pens in an inkbottle again and again. Reed pens had a blunt end; their squared-off strokes can be distinguished from the finer and more delicate strokes of a quill pen. Van Gogh often used both. Sometimes he began with a pencil sketch and drew with pens over it. He did not trace the pencil lines; they were more of a road map. He did not erase them afterwards, but allowed them to remain visible. The style Vincent used in his drawings carried over into his oil paintings where he also employed short, blunt strokes. When using a reed pen, that type of stroke was a necessity, when painting in oil, they were his choice. These two drawings, Starry nights and Wheat field with cypresses, later to become iconic oil paintings, show the variety of marks that van Gogh employs to describe texture and form. The whole drawing area is completely covered with a particular mark doing a particular job. The way that the starlit sky in ‘Starry Night’ is described simply with lines is quite fascinating. But looking closer to see that the lines are a wide variety of thicknesses and strengths of ink and flow this way and that to almost give a sense of movement in the heavens. Add to this the colour of the oil version and you have another painting full of life.

Even though he suffered major epileptic seizures in December of 1889 and January of 1890, he continued to work profusely during the winters. He also exhibited more work, one and only of which was sold in his lifetime. He writes to Theo, ” work is going on well. I’ll be out of doors there. I’m sure that the desire to work will devour me and make me insensible to everything else and in a good mood. And I’ll let myself go there, not without consideration but without dwelling on regrets for things that might have been. I’ve done two canvases of the fresh grass in the gardens, one of which is extremely simple and here’s a quick sketch of it.”

Late January, as a proud new uncle Vincent set out to make more work but suffered another attack. As he moved to the town of Auvers, he stopped in nearby Paris to meet his sister in law and nephew. Under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet, he developed a close friendship and painted some seventy canvases, an astonishing outburst of creativity. He wrote to Gauguin, “Have you also seen the olive trees? If you like something like you were saying about your Christ in the Garden of Olives, not destined to be understood, but anyhow up to that point I follow you, and my brother clearly grasps this nuance. I also have a cypress with a star from down there.

“A last try – a night sky with a moon without brightness, the slender crescent barely emerging from the opaque projected shadow of the earth – a star with exaggerated brightness, if you like, a soft brightness of pink and green in the ultramarine sky where clouds run. Below, a road bordered by tall yellow canes behind which are the blue low Alpilles, an old inn with orange lighted windows and a very tall cypress, very straight, very dark.” Vincent writes to Theo with certain finality in his subconscious.

In summer of 1890, on 27th July, his life ends in farmhouses and fields in the northern town of Auvers with billowing clouds of coiled toppling lines, like tumbling putti, made with watercolors and oils, imitating the staccato patter of reed pens. In an old vineyard, under a baby blue sky, chickens scratch in the cool shade of a pergola. Van Gogh sketched this not long before he shot himself, when, he told Theo, “As for my own work, I risk my life for it and my sanity is half shot away because of it.” It is the accomplishment of somebody who finally discovered how to make the hardest thing he had ever tried to do look easy. What looks so simple was the result of years of practice, patience and perseverance that went into his works. And in the end while looking for hope for his brother in his art, after his life, as he shot himself, he wrote, “I still love art and life very much.”

Bibliography

1. Anna Suh, Vincent Van Gogh; A self-portrait in art and letters, 1st edn. 2006, Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, New York. ISBN10-1-57912-586-7

2. John Berger (edited by Jim Savage), Vincent (Sept 2005), Berger on Drawing, 2nd edn, Ireland: Occasional Press. ISBN978-0-9548976-3-5

3. Graham Rich, Van Gogh, 2nd edn, Tick tock entertainment, Great Britian. ISBN1-86007-455-3

4. Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker, Vincent van Gogh – The Letters, First published 2009, Thames and Hudson, London, ISBN 9780500238653

5. Ives, Colta, Susan Alyson Stein, Sjraar van Heugten, and Marije Vellekoop, with Marjorie Shelley, Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings, 1st edn (2005), Met Publication,

6. Ronald de Leeuw, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, 1st published (March 1, 1998), Penguin Classics, ISBN-10: 0140446745.

7. Steven Naifeh, Gregory White Smith, Van Gogh: The Life, Reprint edition (December 4, 2012), Random House Trade Paperbacks; ISBN-13: 978-0375758973

8. Irving Stone, Jean Stone, Dear Theo: The Autobiography of Vincent Van Gogh, 1st edn, (September 1, 1995), Plume book, NYC, ISBN0452-27504-0.

9. Irving Stone, Lust for Life, 50th anniversary edition (June 1, 1984), 50th anniversary edition (June 1, 1984), ISBN-13: 978-0452262492.

Websites

//vangoghletters.org/vg/bookedition.html (accessed March 2014)

//www.yuricareport.com/Art%20Essays/VincentAsDraftsman.html (accessed March 2014)

//www.vangoghgallery.com/ (accessed March 2014)

Journals

Michael Kimmelman, The Evolution of a Master Who Dreamed on Paper, October 14, 2005,Art Review, Vincent van Gogh, New York Times.

Martin Gayford, winter 2009, The Real Van Gogh, RA magazine, No. 105, winter 2009.

Martin Gayford, Ann Dumas, Behind the scenes, RA magazine, winter 2009, No. 105, winter 2009.

Good Article!

Thanks

Good Article – because it reminds me the Drawing Academy Lessons (26)

and excites and inspires me to redraw or to copy some drawings from the Article as Exercises of Drawing Academy Assignments – a sketching the Old Masters.

Fantástico.

Many years ago I went to a large exhibit of this genius’s paintings. The energy in his paintings combined with mine and I found I never wanted to leave the exhibit. As with his paintings, I found my energy rising to join him in his drawings. I truly need to spend more time with his work. Thank you for your article.

good article.