Article by Slater Smith

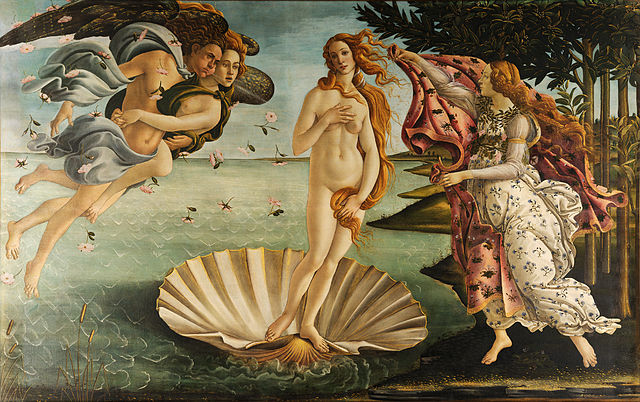

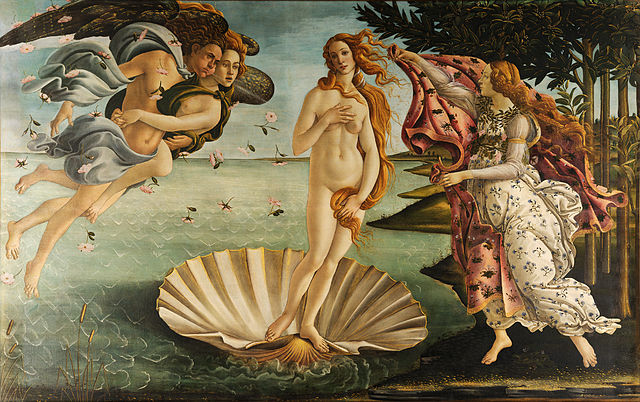

The Renaissance was one of the greatest periods in art history. Man lost the teachings of the Ancients during the Middles Ages, but was able to not only renew, but to improve upon them. We think of Raphael’s monumental frescoes, Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus”, and Michelangelo’s awe-inducing sculptures. They must have been gifted. They must have been talented from birth. They must have had divine motivation or inspiration to reach such heights. Or so we think. The artist was not much during the Renaissance. In fact, “artist” was a word nearly floating into obscurity. They were simple craftsmen trying to make a living, just like a normal man. Not as moving of a purpose as the modern world would expect.

This leads to the question of why someone would choose to be a craftsmen. Simply put, they did not. For many people, painting was a family business. If your father and grandfather painted, then so would you. For others, it was a sound career decision, probably made after noticing a father noticed his son having some basic skill for the art. Leonardo da Vinci was most likely apprenticed due to his illegitimate birth and drawing in his free time.

To begin their careers, boys – not any girls – were sent away in their early teens to a master’s workshop or guild. It was there they learned not only how to paint, but a number other other trades. It was commonplace for an apprentice to be able to carry out a wide variety of artistic tasks. They would sculpt and cast statues, design weapons, grind pigments to make paints, and so on.

Now then, how exactly did the pupils learn the basics? In the beginning, they copied the works of their master, learning how to draw from life later on in their studies. During the Renaissance, the ability to copy was an important one. In that time, art was a business, first and foremost, and teamwork in crucial in a business. In order to complete the many commissions a workshop would receive, the master needed the hands of his students who assimilated his style. The teacher often design the composition and paint the subjects in a piece, leaving it to the apprentices to work on the fine, laborious details.

The time in which someone stays at a workshop changes from person to person. Some study for only a few months. Cennino Cennini, a craftsman in the 1300s, suggests that one should train for a minimum of half a dozen years! After achieving mastery, a painter can go on to set up his own workshop, perhaps in other town or country, and take in his own apprentices.

You might think that, after becoming one of the greatest of painters, a master would achieve fame and fortune. That is not always the case. Very few painters ever reached that divinity. Many remained as a sort of local legend. Only a handful of artists were widely known for their skill, the earliest being Giotto. Even then, they usually lived in their workshop or had a middle-class home, the former being the most typical. Other than that, artists lived relatively normal lives – they get trained, earn a living, and pay taxes just like anyone else. It was not until the end of the Renaissance that sculptors and painters were hailed for their craft.

In the succeeding years, art began to change dramatically. Painters began to specialize in painting and working on their own. Academies were opened across Europe for, after many years, both the man and the woman. Artists were focusing on style and politics, but, at the same time, ascended to heights that that the average Joe or Jane thought to be inaccessible. To be an artist, you need talent. If you do not have talent, then give up any hope of mastery. The Renaissance begs to differ. In that time, art was just a skill that, with proper training and practice, anyone can master, especially a beginner.

Madonna of the Stairs, Michelangelo’s earliest known piece