Article by Sarah

As the story goes, one sunny morning in Florence, Italy, Filippo Brunelleschi appeared at the gate of the not-yet-completed cathedral, holding a little painting and a little mirror. Already considered a magician by half of Florence because of the dome he was building without any scaffolding, Master Filippo gathered a sizable crowd for his demonstration.

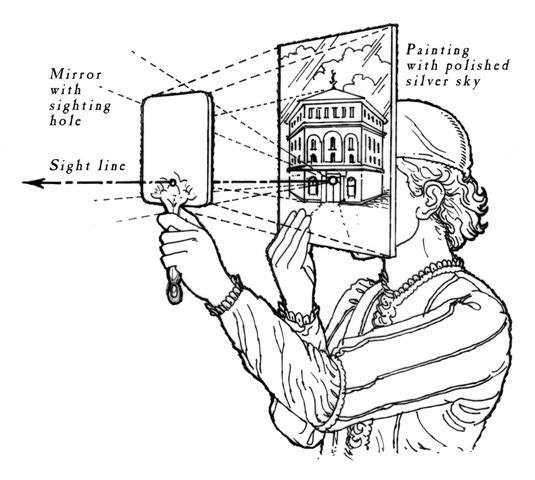

Brunelleschi led the crowd to the gate of the cathedral so that they would look in the direction of the Baptistery outside the building. He gave a painting with a hole in the middle to somebody in the crowd and asked him to keep the unpainted backside of the painting towards himself and to look through the hole with one eye into the direction of the Baptizing Chapel. Then the master suddenly lifted a mirror in front of the painting, covering the chapel from the viewer’s sight, and asking loudly enough so that people further away in the crowd could hear: “What can you see, Sir?” “Oh, the Baptistery, Sir Filippo!” the man replied.

The audience was amazed. On the other side of the painting, the chapel was depicted perfectly and the hole was right on the horizon, just at the vanishing point. So the mirror showed just the same as the reality it covered.

Painting of Brunelleschi by Masaccio

Filippo Brunelleschi, one of the most famous architects who ever lived, was born in 1377 in Florence, Italy. Brunelleschi’s early life is mostly a mystery. It is known that he was the second of three sons and that his father was a distinguished notary in Florence, Because of this, Filippo’s family had a good deal of money and was able to give him a fine education. Brunelleschi initially trained as a goldsmith and sculptor and enrolled in the Arte della Seta, the silk merchants’ guild, which also included goldsmiths, metalworkers and bronze workers. Around the turn of the century, he became a master goldsmith.

In 1401, Brunelleschi competed against Lorenzo Ghiberti, a young rival, and five other sculptors for the commission to make the bronze reliefs for the door of the Florence baptistery. Brunelleschi’s entry, The Sacrifice of Isaac, was the high point of his short career as a sculptor, but Ghiberti won the commission.

Perhaps Brunelleschi’s disappointment at losing the baptistery commission might account for his decision to concentrate his talents on architecture instead of sculpture. But little biographical information is available about his life to explain the transition. Also unexplained is Brunelleschi’s sudden transition from his training in the Gothic or medieval manner to the new architectural classicism. Perhaps he was simply inspired by his surroundings, since it was in this period (1402-1404) that Brunelleschi and his good friend and sculptor Donatello purportedly visited Rome to study the ancient ruins.

Speaking of this transition, historian Vasari writes: “…but gave himself no rest until he had considered all the difficulties of the Pantheon and had noted and drawn all the ancient vaulted roofs, continually studying this matter, and if by chance they found any pieces of capitals or columns they set to work and had them dug out.… Neither did he cease from his studies, until he had drawn every kind of building, temples round and square and eight sided, basilicas, aqueducts, baths, arches, and others, and the different orders, Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian, until he was able to see in imagination Rome as she was before she fell into ruins.”

Photo of the baptistery

Some time after 1410 architect Filippo Brunelleschi worked out a ‘new’ way to depict three-dimensional objects or scenes on a two-dimensional (flat) surface. Brunelleschi called his method perspective; known to ancient Greeks and Romans, but lost during the Middle Ages. To those in his era his discovery appeared to be like making magic. Brunelleschi had noticed that the parallel stripes of the green marble on the angled sides of the baptistery in Florence seemed to get closer together the farther away they were from the viewer.

He developed a mathematical system whereby an artist could convincingly re-create this effect on a flat surface to give illusion of distance. With these principles, one can paint or draw using a single vanishing point, toward which all lines on the same plane appear to converge, and objects appear smaller as they recede into the distance.

Nearly every Renaissance artist wanted linear perspective—a way of creating an accurate illusion of space that could match the new naturalism then being applied to the human figure. Florentine painters and sculptors became obsessed with it.

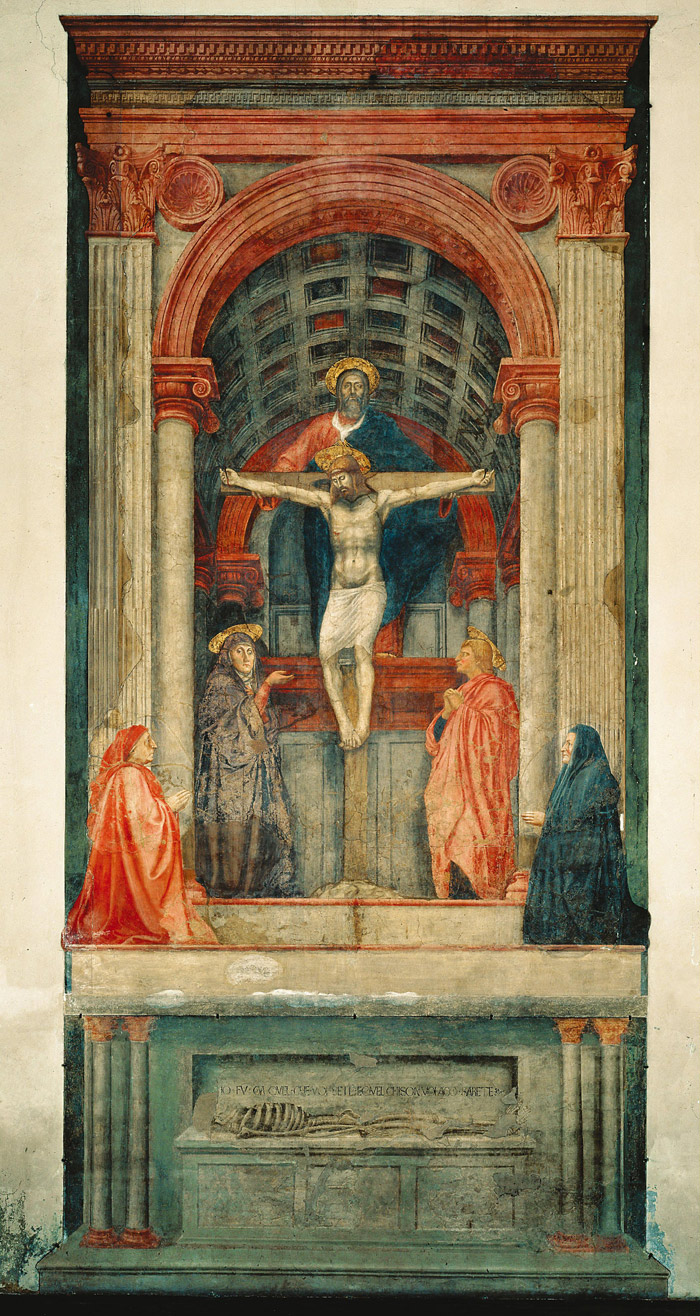

Masaccio’s “Holy Trinity” 1427

Masaccio’s contemporaries were struck by the palpable realism of the ‘Holy Trinity’ fresco, as was Vasari who lived over one hundred years later. Vasari wrote that, “The most beautiful thing, apart from the figures, is the barrel-vaulted ceiling drawn in perspective and divided into square compartments containing rosettes foreshortened and made to recede so skillfully that the surface looks as if it is indented.”

Pietro Perugino’s fresco at the Sistine Chapel (1481–82)

Brunelleschi’s ideas became well known after architect Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) published them in 1435 in his book entitled On Painting.

Linear perspective, as a novel artistic tool, spread not only in Italy but throughout Western Europe. John Berger, an art historian, notes that the convention of perspective fits within Renaissance Humanism because, “it structured all images of reality to address a single spectator who, unlike God, could only be in one place at a time.”

In other words, linear perspective eliminates the multiple viewpoints that we see in medieval art, and creates an illusion of space from a single, fixed viewpoint. This suggests a renewed focus on the individual viewer, and we know that individualism is an important part of the Humanism of the Renaissance.

Use of linear perspective quickly became, and remains, standard studio practice today.

Interesting article.